You probably have learned how to find the area enclosed between the function f(x) and the axes, or between 2 functions. You have also learned the volume of revolution for a function f(x) with the x or y-axis as the axis of rotation. In this section, you’ll be learning 2 new applications, which are the arc length and the surface area of revolution.

ARC LENGTH

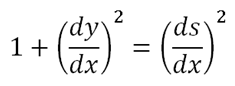

Consider 2 points, P and Q, on a curve. P is the point (x, y) and Q is the point (x + δx, y + δy). Let s be the length of the arc from a point on the y-axis, and δs the length of the arc PQ. Since δs is very small, we can approximate the arc PQ to a straight line. Hence, using Pythagoras’ theorem, we have

(δs)2 = (δy)2 + (δx)2

and after square-rooting both sides, we end up with

The parametric form of s can be obtained by dividing the equation (δs)2 = (δy)2 + (δx)2 with (δt)2. While the polar form is probably not in your syllabus, so don’t worry too much. To find the arc length of a particular function, just differentiate it with respect to x, then substitute it in the formula above.

SURFACE AREA OF REVOLUTION

Let A be the area of the surface formed by rotating the curve y = f(x), between the lines x = a and x = b, about the x-axis. Let the curved surface area of a blue ring shown be δA. Treating the strip as being bounded by 2 cylinders, we have

2πy δs ≤ δA ≤ 2π(y + δy) δs

which gives us the formula

Again, differentiate the function, and substitute it into the formula to find the surface area of revolution.

Note that square root functions are hard to integrate. Therefore, you need to practise more on doing such functions if you want to score well in this section. A typical Further Mathematics paper probably has most questions on this chapter, so it is good that you master it. That’s all for this chapter. ☺

No comments:

Post a Comment